Edge carbides

Recent › Forums › Main Forum › Techniques and Sharpening Strategies › Edge carbides

- This topic has 21 replies, 6 voices, and was last updated 04/15/2017 at 8:54 am by

Readheads.

-

AuthorPosts

-

04/06/2017 at 3:52 pm #38200

I have been doing some research on metal grain and carbide sizes. It seems like they are in the 1-10 micron range max. That being said as we go down to the 0.1 micron diamond films and assuming we are still abrading vs. burnishing, I would expect that we are “breaking into” individual grains and carbides at the edge.

Does anyone know of any SEM work done to examine this ?

04/06/2017 at 7:39 pm #38203No, I don’t know of anyone currently doing that though we should ask Todd Simpson. It is definitely something I’d like to study more.

-Clay

04/07/2017 at 2:52 am #38207Very good question. I don’t know if any research has been done into it, but you might want to check Scienceofsharp and Cliff Stamp.

Molecule Polishing: my blog about sharpening with the Wicked Edge

04/07/2017 at 9:45 am #38219I am writing this as a mental rant to generate discussion. I am not sure what I want out of this except maybe a collaborated wiki post which is the closest thing we could get to a peer reviewed journal paper.

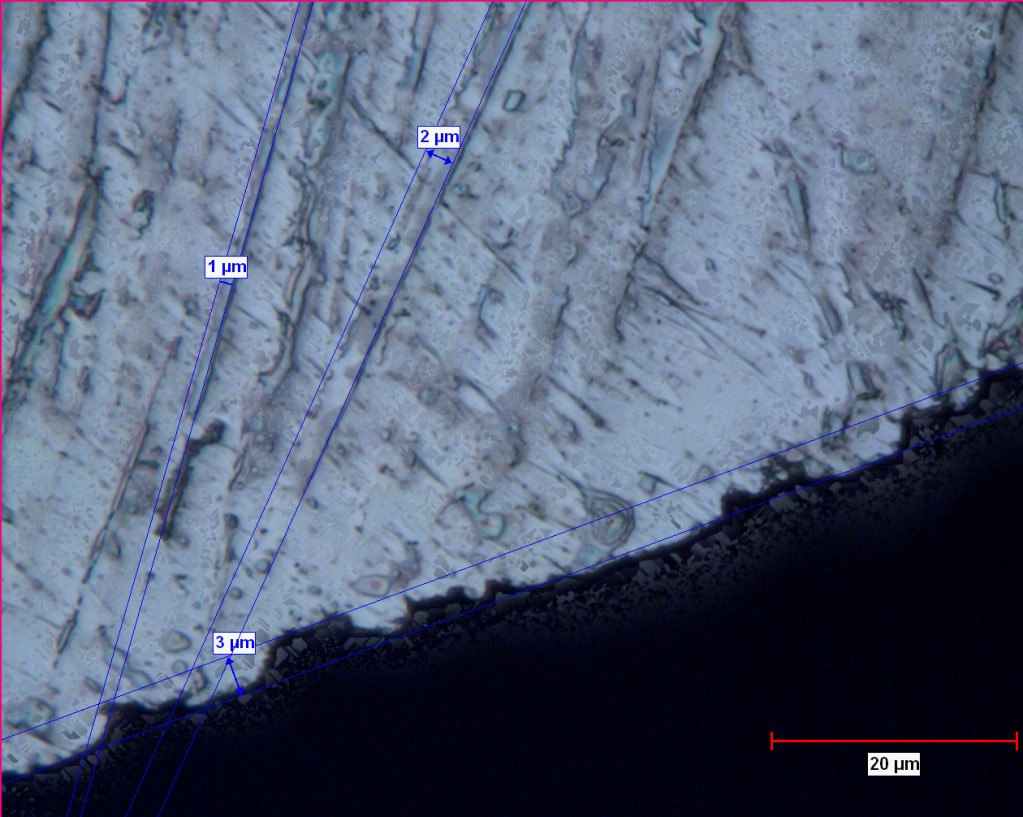

Below is an image I found on bladeforums. It is endorsed by Lagrangian (ie. Anthony Yan). Pretty fascinating although it is a single piece of evidence and I don’t even know what kind of steel it is, etc. A couple of amateur initial observations:

- The matrix of martensite and retained austenite is clearly visible

- Primary carbides on the order of 1-5 microns clearly visible

- Secondary carbides in the nanometer range are not visible

- The edge topography “seems” to be a function of the primary carbides.

- The microchips seem to have exposed primary carbides left behind embedded in the martensite

- Additional independent micrographs are needed to validate what we “think” we are looking at

After a quick reminder from my research chemist daughter about metals and the different types of bonding within the “electron clouds” of steel as well as some research into Electron Microscopes (SEM) (Cornell has great equipment and information) I think the following:

There are quite a few different bonding interfaces within steel, namely, interstitial carbon within the iron atom, intergranular (the bonds which hold an individual grain together), intragranular (bonds between grains), bonds within a carbide, bonds between carbides and grains, bonds between carbides, etc. I understand that the mechanism for what will most likely bond with something else is a function of the electron energy level (electron volts – eV) as well as other things like heat treat temperature, quench and the rates associated with them. While electrons are all the same, their energy levels are not. I’m pretty sure that the SEM takes advantage of this and uses this phenomena to generate images (oversimplification). It would seem to me that the SEM data could be used to quantify various bond strengths. Cornell now has a new type of SEM called the Electron Microscope Pixel Array Detector (EMPAD). Per their press release:

The electron microscope, a powerful tool for science, just became even more powerful, with an improvement developed by Cornell physicists. Their electron microscope pixel array detector (EMPAD) yields not just an image, but a wealth of information about the electrons that create the image and, from that, more about the structure of the sample. “We can extract local strains, tilts, rotations, polarity and even electric and magnetic fields,” explained David Muller, professor of applied and engineering physics, who developed the new device with Sol Gruner, professor of physics, and members of their research groups.

It also seems to me that as we abrade and burnish the edge with the Wicked Edge System down to 0.1 diamond films that we “must” be defeating every one of these different bonds to remove metal. Being that the pressure (force/area) we exert on the very edge defeats these bonds, it would seem to me that we are introducing residual stresses into the matrix which cannot be good (albeit unavoidable). I wonder if the sharpening process itself sets the edge up for failure.

It amazes me that after quite a bit of research into the science via the peer reviewed journals on metals that the physics about what is going on in not fully documented. I pretty much take the various forums with a grain of salt because it usually gets into bar-style talk about the evidence of failure modes.

I clearly understand that all of these edges are sufficient for what we use the edge for (kitchen for me), however, the failure mode of chipping is what interests me. There are millions of kitchen knives out there and it seems like every one I get to look at with my USB scope at 250x have chips. We all think we know why but do we really know why. What can be done to improve it ?

If I had a chance to do my engineering career again, I would consider the Metallurgy department at Cornell – LOL

Attachments:

You must be logged in to access attached files.

04/07/2017 at 11:41 am #38223I located the Spyderco posts that the above photo came from. It’s from a guy named Clip. Lots of good stuff but it is never brought to a true conclusion relative to the edge carbides. Near the end of the post Clip got a new job and lost access to the metallographic equipment (1000x). He also never did Nitrol etching. He did state that you can do it under a 100x scope to see the grains and carbides. I think I will try it.

http://www.spyderco.com/forumII/viewtopic.php?f=2&t=54864

Attachments:

You must be logged in to access attached files.

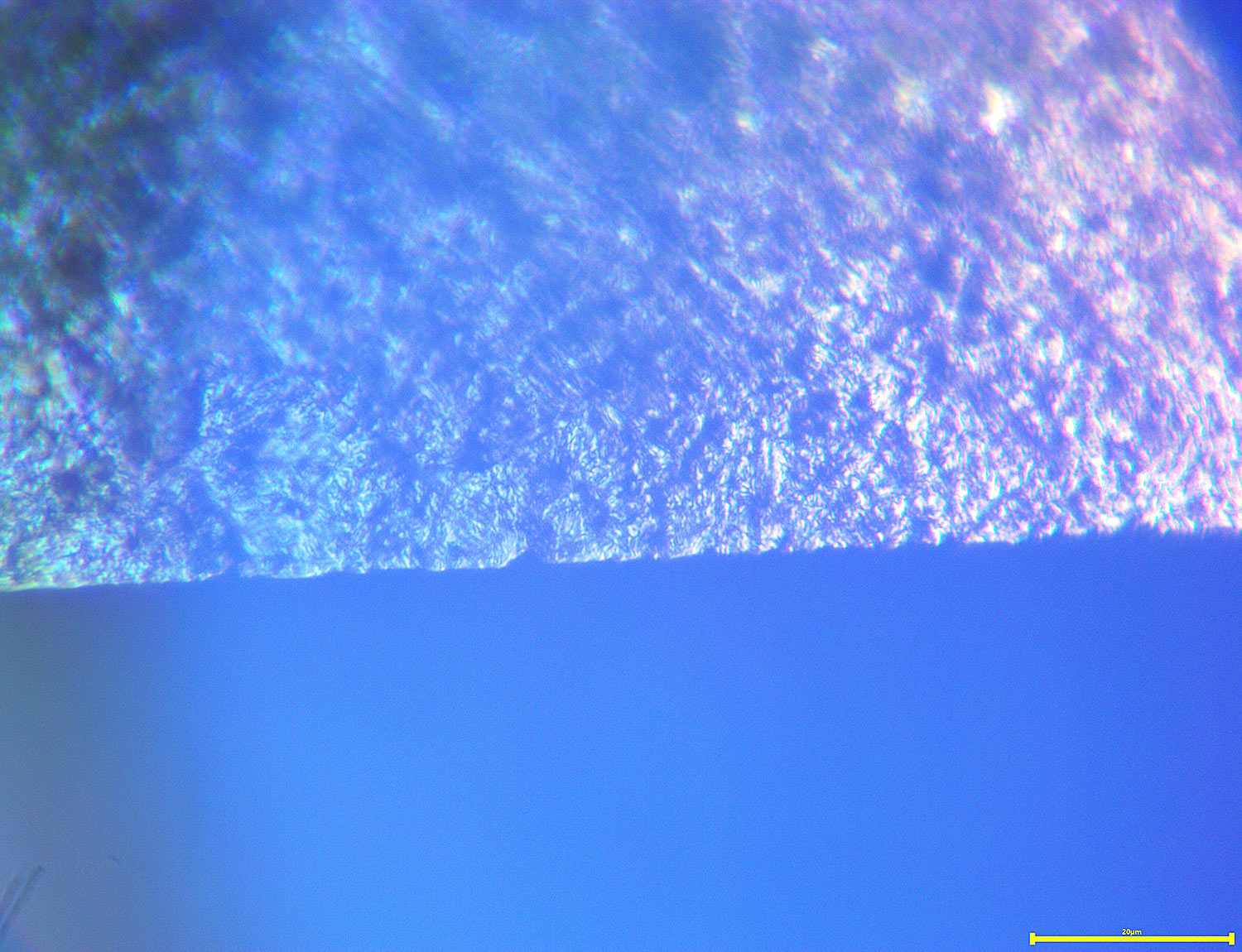

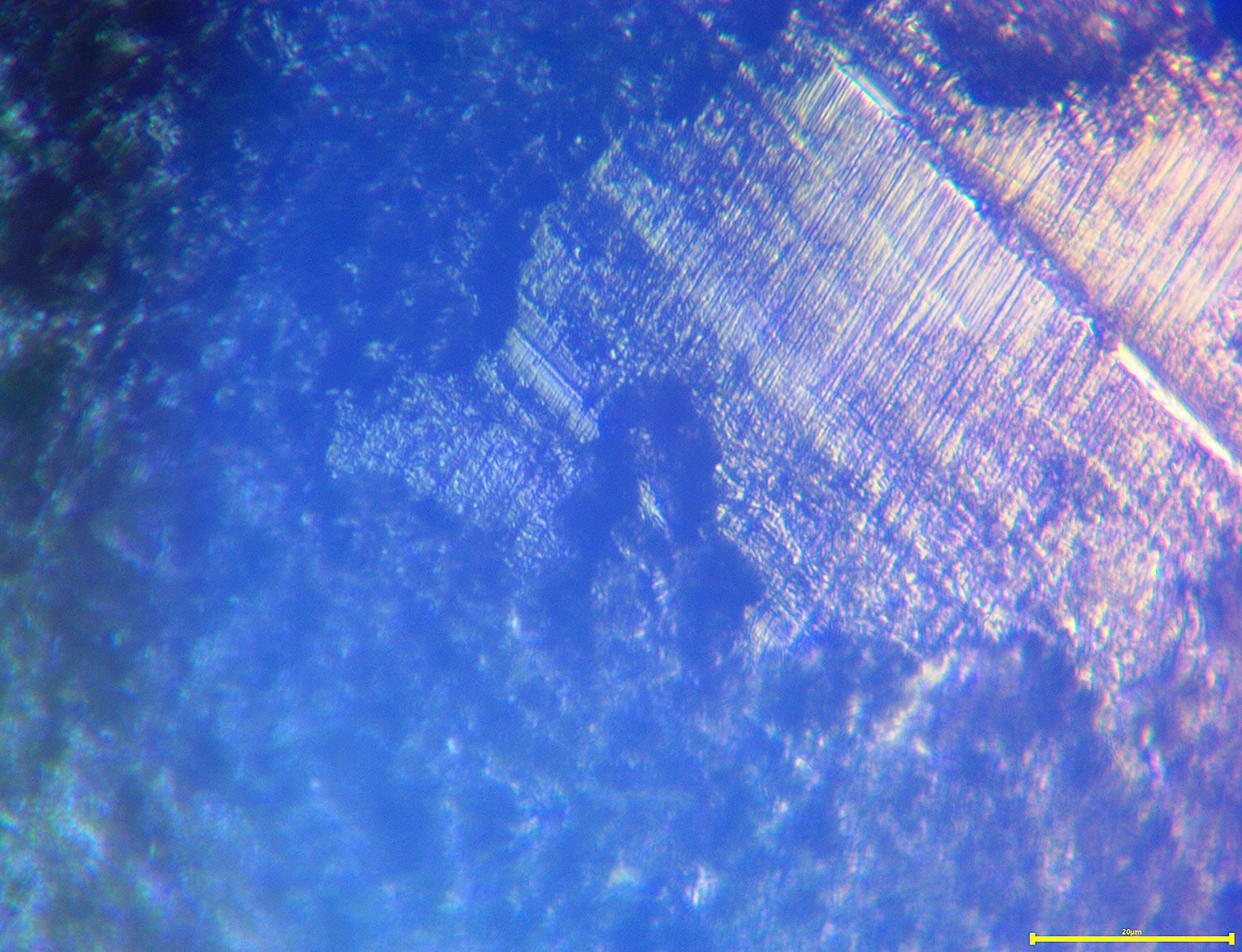

04/07/2017 at 1:31 pm #38226This got me curious and I decided, very un-scientifically, to a sample blade that had been sharpened/lapped to .5 microns. To the naked eye it had a mirror finish. I grabbed some PCB etchant, which I think is ferric chloride, because that’s what I had, added some alcohol and swirled the blade in it for a while, then cleaned it off. It’s shocking how much metal was removed! Here are some quick pics at 2000x:

In the second image, you can see the old surface with the scratch pattern as a little plateau. Around that area you can see the very granulated surface at a lower depth, showing how much metal was dissolved. In the first image, the edge is starting to corrode and is showing little chips which were not present before etching. I’m not sure yet what inferences to draw, but I do think there is some valuable information if we can decode it.

-Clay

Attachments:

You must be logged in to access attached files.

04/07/2017 at 1:48 pm #38230What kind of steel is it ? Probably need to know the expected grain size.

In researching metallography it sounds non-trivial. Certain metals react better with certain etchants. Examination under 100x is the norm.

Based on grain size alone, I am pretty sure we are sharpening “within” grains and “hope” we expose secondary carbides within grains for best wear resistance. I’m thinking that the primary carbides between grains are just getting in the way.

04/07/2017 at 3:14 pm #38233Attachments:

You must be logged in to access attached files.

04/08/2017 at 7:15 pm #38272Carbides are pretty darned hard, but still not quite as hard as diamonds, so at the 0.10 micron level of diamond abrasive, you should be cutting through/into the carbides.

I agree with redhead in the OP that carbides are in the 1-10 micron range. I actually have an unscientific belief that carbides are in the 1-4 micron range based on my oh-so-very-fun experiences with carbide popout.

It is possible to abrade most abrasion resistant/carbide forming steels with just about any low grit abrasive medium, such as sharpening stones, belts, etc.. You don’t need diamonds at that level because your abrasives are basically digging out chunks of matrix steel, which includes the carbides with them, so it’s like a backhoe digging into the ground, and bringing up a bucket full of dirt and rocks all together. As you approach the 10, or 4-1 micron range, you begin pulling up more rocks and less dirt, which is where the abrasion resistance kicks in since the carbides are either harder than or equal to the abrasive media (Aluminum oxide is mohs ~9.5, SiC, which is itself a carbide is about 9.7, CBN is 9.9 and diamond being 10) The carbides range from about 9 to 9.9, so the backhoe is trying to dig out a rock that is bigger than the bucket.

So at the 4K-10K level of sharpening, your scratches are arguably the same size as the carbides, which is where you will start needing a harder abrasive to cut through the carbides and matrix steel equally.

2 users thanked author for this post.

04/10/2017 at 3:15 am #38293Wow! We keep getting deeper into this “rabbit hole” each year LOL! Aaaaa, the pursuit of the “perfect edge” is addictive and almost like a drug….. We all need help.

Eddie Kinlen

M1rror Edge Sharpening Service, LLC

+1(682)777-162204/10/2017 at 8:39 am #38296Interesting… Sometimes you knock the carbides out (I do have experience

) and sometimes you keep sharpening through the carbides. How come? Is it the bond between the carbides and the surrounding material? Is it the steel?

) and sometimes you keep sharpening through the carbides. How come? Is it the bond between the carbides and the surrounding material? Is it the steel?Molecule Polishing: my blog about sharpening with the Wicked Edge

04/13/2017 at 7:59 am #38386My questions arose when reading the document “Metallurgy of Steel for Bladesmiths – by John D. Verhoeven”. It is a complimentary work to the “Experiments in Knife Sharpening – by John D. Verhoeven” which is on the WEPS download page. It is 200 pages, fascinating reading, and gets into the why’s and wherefores of carbides and everything else. I put it on my Google drive (link below) with full sharing (hope it works).

I am personally looking for a new 8″ chef knife with a wide body (2.375″) and custom fit handle. Right now I am thinking of 440C or CPM154 steel with full cryo (Jay Fisher has me believing) and my budget for this custom knife is around $500. I am going to do this once and I want to do it right. It comes down to the proven reputation of the knife maker relative to the quality of the steel he buys (not all 440C is the same) AND his specific heat treating details. This is what drives the grain sizes and carbides (some are good, some not so good). I have inquired on Bladeforums and just get a lot of trust me responses. Since I trust you guys I wanted to solicit your advice. What do you think ?

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/0B5t7FJ9Zmj1hZ2hiZUx1Y3JKMTA?usp=sharing

1 user thanked author for this post.

04/13/2017 at 8:18 am #38388You might also want to ask the question on http://www.chefknivestogoforums.com/ and http://www.kitchenknifeforums.com/forum.php , which are two forums specialized in kitchen knives. And you can look on my blog on this subject, of course

: https://japaneseknifereviews.wordpress.com/ .

: https://japaneseknifereviews.wordpress.com/ .Personally I wouldn’t go for CPM154 or 440C if I had such a budget. You can get a cheap custom chef’s knife for that money or a (very) expensive production knife. My favorite stainless steel for kitchen knives is AEB-L or its equivalent 13C27. (To stay on topic: very small carbides.) There’s no stainless steel I can get sharper. If you want to go for edge longevity, you may want SG2 or R2 (which I think are the same), which are getting quite popular in kitchen knives. Or even ZDP-189, although this isn’t the toughest steel (certainly for a chef knife some toughness is important, too). If you want a carbon steel, go for aogami super. You can get it nearly as sharp as white steel (which is the steel I can get the sharpest) and it’s got good edge retention and toughness, too.

Molecule Polishing: my blog about sharpening with the Wicked Edge

1 user thanked author for this post.

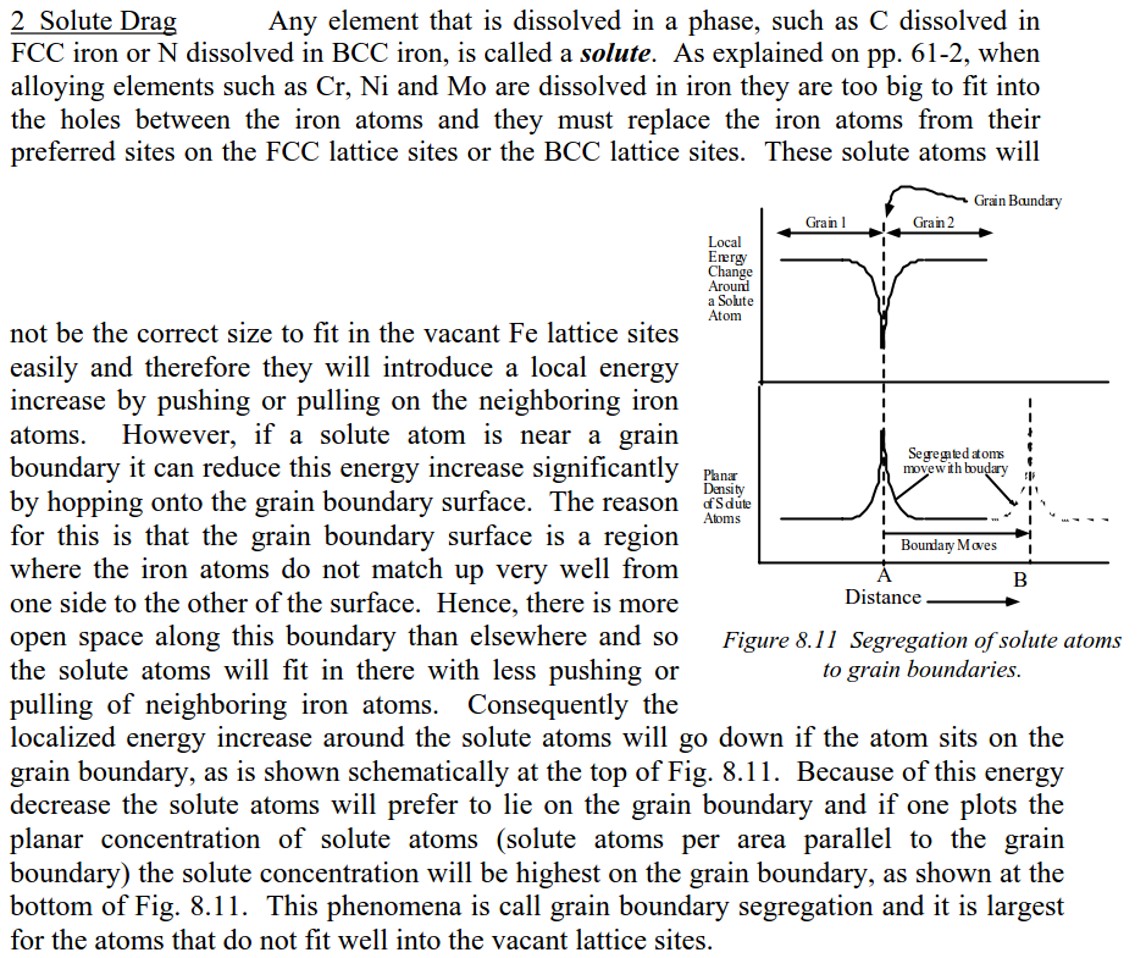

04/13/2017 at 12:22 pm #38399As an example of the excellent explanations in Verhoeven’s Metallurgy paper — here is his description on where the primary carbides end up in the steel matrix. My thought is that if the energy levels (bonding) are lower than those within the steel matrix (and also lower than within the carbide) then the carbide will be more likely to “rip” out whole vs. being sharpened/smoothed itself. I concur that we all pretty much know this but my interest is in knowing exactly why.

Attachments:

You must be logged in to access attached files.

1 user thanked author for this post.

04/14/2017 at 3:47 am #38404Thanks a lot for your reference to “Metallurgy of Steel for Bladesmiths”. His “Experiments on knife sharpening” is a classic here, but I didn’t know this book.

Unfortunately I’m not a chemist or metallurgist, but I could more or less understand this quote.

As an example of the excellent explanations in Verhoeven’s Metallurgy paper — here is his description on where the primary carbides end up in the steel matrix. My thought is that if the energy levels (bonding) are lower than those within the steel matrix (and also lower than within the carbide) then the carbide will be more likely to “rip” out whole vs. being sharpened/smoothed itself. I concur that we all pretty much know this but my interest is in knowing exactly why.

I guess my question is more or less the same as yours. Although it would be nice to know exactly why, it would for now be enough for me to know when. In other words: in which steels are carbides less likely to being ripped out vs. being sharpened.

Molecule Polishing: my blog about sharpening with the Wicked Edge

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.